Control and Loss

Wednesday, 2012-01-04; 13:19:30

One night, while traveling in Goa, I had a dream about my brother. I don’t usually remember what happens in my dreams, and if I do, only little. Sometimes I experience a vague emotional feeling from dreams for a few hours, even if I don’t remember specifics. I once tried to keep a journal at my bedside to remember details before they slipped away during those first few hazy seconds of consciousness. I never got farther than three or four entries.

For this dream, the only detail I remembered was an observation I made to my brother. I said to him, “Wait, you’re not supposed to be here. You’re dead! This must be a dream.” It was a bizarre and sobering moment of lucidity. And then I awoke.

I was in a melancholy mood for the rest of the next day. I cried during an autorickshaw ride. I thought about him while walking with my friend along the beach in the afternoon.

I had that same feeling only once before, while moving out of the apartment that he and I shared for the one and a half years before he died. I moved most of the stuff by myself for the whole day, and for about six hours post-midnight. Almost finished, I sat down on the white rug in his ~100 sq. ft. room. I looked around at the full-length mirrors of his former closet, along the same wall as the door to his room, where his extensive collection of jackets, collared shirts, and shoes used to reside, and at the place where his old bed — an old wooden heirloom, almost 100 years old, which belonged to my great-grandparents at one point, now mine — used to sit, across from the closet. In the other corner opposite the door used to be a round, wooden coffee table that he used as his nightstand — also now my nightstand — and an old, white conservator’s light on a swing-arm. I can remember that round table for as long as I’ve been alive.

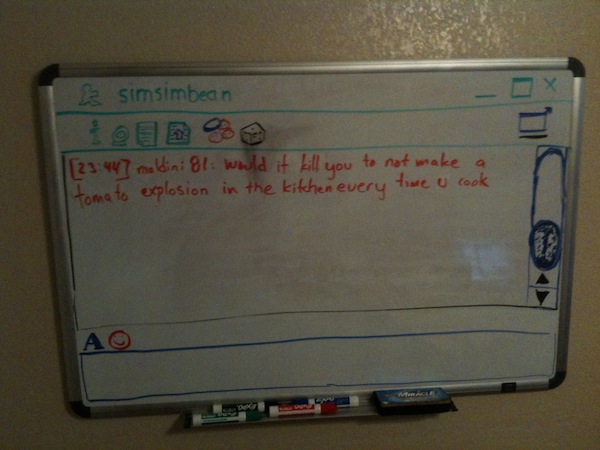

As I was sitting there, looking at the empty room, it felt like I was leaving him behind. Like this apartment — where we shared many laughs about the poorly-edited notices from the property manager, had drunk discussions with his friends about religion, and had “IMs” with each other on the kitchen whiteboard — would forever be the tomb for his memories. That the physical space where we shared those memories is where they are stored.

I’ve experienced the death of someone before, of a grandfather, an aunt, and a couple great aunts and uncles, but never with someone with whom I’ve shared the vast majority of my life. Gianni was there when I was a toddler, throwing balled socks up in the air to make me laugh. He was there when we launched model rockets with my uncle in Seattle, when the rocket stuck to the launch pad and burned a hole through it. He and I organized a party at my parents’ house when they were away, just a few years ago, when his friends and I made fun of him by dressing me the way he used to. Even when he was a pilot for a charter airline on the east coast, he would frequently return home, and I would pick him up from the airport in the beat-up 1986 Honda Civic we shared.

Experiencing the death of someone close is an intensely emotional experience. I’d always heard about the five stages of grief. For me, there was only one stage: sadness. First, sadness, at the hospital with friends and family, seeing everyone crying, not allowing myself the same luxury of breaking down. Then, extreme sadness, for the next few days, when his death really hit me, when I wanted to be by myself, away from everyone who wanted to comfort me. Then, less sadness.

Everyone is also quick to offer condolences, and I know they mean well. But it always comes off as being sad or trite: with some, I can tell they’ve experienced what I’ve experienced, and I know they’ve gone through what I’ve gone through, felt what I’ve felt. You can hear it in their speech, see it in their eyes. And that makes me sad, that so many other people experience this. With others, you can tell they haven’t yet experienced this, that they just don’t understand. So their words ring hollow. It’s an emotional reaction, but it’s how I react nonetheless.

The best way I have to cope is to be hyper-rational. It’s not my fault. I couldn’t protect him every second of every day. He lived for 30 years, short by contemporary standards, but, historically, long. And, most importantly, I was close to him for the last 1.5 years of his life. The last thing I said to him was, “You make breakfast, I’ll make lunch”, as we planned for Father’s Day the next morning. I watched him walk away in his motorcycle jacket for a few seconds, then turned around and went back into our apartment.

The most lasting feeling from my brother’s death, though, is the profound lack of control. It’s simultaneously extremely disconcerting and comforting. I fear the possibility of death more acutely now. I think about scenarios for my demise in everyday life. What if a driver suddenly loses control while I’m standing on the curb, and starts careening towards me? Which way will I run? What if someone pushes me on to the train tracks while the train approaches the station? How can I prevent it? How will I get out of a crashing plane? Would there be a parachute on board? When is the optimal time to jump out? I’ve actually thought about these questions.

But then I think about how long I’ve lived without even considering such events. How, for the most part, cars stop at red lights and stop signs to let me cross. How doctors agree to check my symptoms and prescribe me medications that not only aren’t harmful, but will cure my ailments. How I can do work, in exchange for money, which I can in turn exchange for food, clothing, and shelter. How society functions by certain rules that allows most of us — excluding, sadly, my brother — to live long, healthy lives.

Two days after my brother died, I went up to my friend’s house in San Francisco. Looking out over the city from his apartment on a hill, people were still walking to work, tall high-rises stood where they always have, the obnoxious, constant ringing of the cable car bells could still be heard as they passed by. Nobody noticed my brother’s death. Nobody noticed my grief.

Far from being painful, it comforted me. The city, a living entity, continued on, unconcerned with the death of one person important to me. Death is a normal part of life. It happens, we deal with it, and move on, keeping memories of events past. This is how it was, it is, and always will be.

So I keep the memories. And laugh when something reminds me of them. At the silly images and videos from the Internet that we would exchange with each other. At the way he would say silly things, mashing together two unrelated words that sounded similar, even from different languages. At his stories of playing practical jokes on flight attendants, asking them to bag lavatory “air samples” for subsequent testing, and of tying a small camera and battery pack to his pet cat in college, viewing the subsequent cat antics in real-time through the TV, in first-person view complete with cat ears. At how we took “butt run” pictures on top of the Leaning Tower of Pisa.

And he loved sports, playing soccer with my dad almost every week. And he loved literature that I have not yet spent the time to read, like Gabriel García Márquez’s “One Hundred Years of Solitude”. And he loved motorcycle riding. And cooking.

And my mom and dad and I, we remember him. We set up an endowed scholarship at his alma mater. In October, we spent his 30th birthday in Firenze, the first after his death. At Thanksgiving, we reminisced about the Thanksgiving-in-a-slice cake that he made a few years ago. And we ate dinner with his friends on the six-month anniversary of his death in December.

And funny cat videos are still traded and viewed by millions. And the apartment we shared is rented out to someone else, unaware of the memories that still linger in the air in his bedroom. And the bells on the cable cars of San Francisco continue their loud, obnoxious rings, oblivious that to one person, they will no longer be heard.

Emotional Supernova Personal Older Newer Post a Comment